Dreams come true

In designing a new flagship, Hamleys brought imagination to life across nine different experience- led worlds of play. How did organisational and experiential strategy impact the brand? Brittany Golob reports.

Blasting off from the ground floor of Moscow’s newest toy store is a rocket ship yearning for the outer reaches of the galaxy – and of children’s imaginations.

London-based international toy seller Hamleys’ Russian flagship is more akin to a theme park or dreamscape than to a toy store. With inspiration drawn from Disneyland, from popular culture and from a simple sense of fun, the new shop shines as a two-storey tribute to the imagination.

“We wanted to develop a new concept of the most fun and interactive toy shops in the world. And our new shop in Moscow delivers this awe inspiring experience for children and families by mixing retail with theme park attractions,” says Mark Drummond, head of marketing and web at Hamleys.

The store opened officially on 31 March in Lubyanka Square – the home of the KGB – around the corner from the Kremlin. Yet, designing the 72,600 square-foot space required a labour of love for those involved at Hamleys and brand and design consultancy Fitch. Aside from the site’s imposing size – it is currently the second-largest in the world and Europe’s largest toy store – its history and location were something to contend with as well. Located in an iconic central Moscow site, the new Hamleys shop occupies the site of a beloved 1950s-era toy store, linking it instantly to Moscow’s own history. The mere fact that it is occupied by a British brand in Russia also influenced the thinking around store design.

These factors were taken into account by the team at Fitch, led by creative director John Regan, as they developed the brand experience strategy for the new store. “Some key things to consider from a Hamleys point of view were things like the fact that it’s a great British brand,” he says, adding that the mentality of thinking like an independent shop , not a store, was a key differentiator. “In the UK, if you go to a store like Toys R Us, you’re thinking big box retail. The experience starts to become a bit disjointed and disconnected from the customer.”

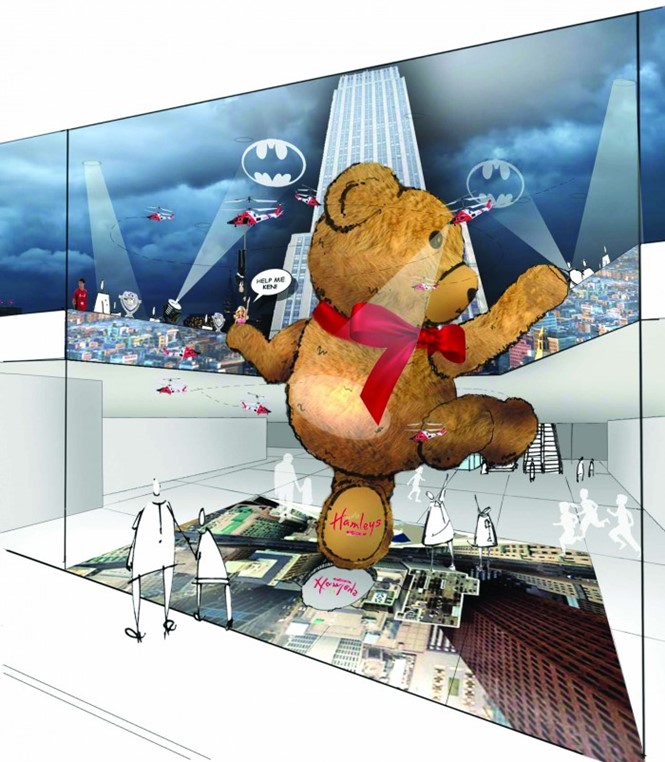

But primarily, Fitch wanted to grab the attentions and spark the imaginations of Hamleys’ main audience: children. Interactivity and live experiences have long been part of the Hamleys promise. Its Regent Street flagship in London is full of demonstrations, performers, hands-on activities and other ways to allow kids to engage with toys.

“If you’re a kid and you go to a store, you don’t just choose something and go home. You want to try things out. It becomes a real experiential centre, locking into kids’ imaginations, where anything can happen.”

The store would take that foundation and push it into the farthest realms of possibility. Instead of a store oriented around promoting sales, this would be a store in which experience was at the forefront. If parents happened to buy toys because of it, so much the better. This version of Hamleys was to be the anti- big box retailer. It was to be a place to explore and discover, not to locate and purchase. In a world defined more and more by efficiency and expediency, this approach to time and attention is a bold experiment.

But, its success stems from the simple fact that the kids are at the heart of the brand. “If you’re a kid and you go to a store, you don’t just choose something and go home. You want to try things out. It becomes a real experiential centre, locking into kids’ imaginations, where anything can happen,” says Regan.

Traditional retail design is secondary to experience. Till points are not static, but roving. Brands take up not single, straight shelves, but worlds of wonder and curving, living spaces. Toys are taken out of the box so that kids can play, not just look. “It’s the kids that lead the way,” Regan adds. “If you can capture the kids you can capture the adults.” This immersive approach also brings a sense of fun to adults too.

The organisational structure behind the design is key. Regan says Hamleys wanted to free up space to allow for play areas and interactive spaces throughout the store. Thus, nine worlds were dreamt up by Fitch – from safaris and princesses to space and storylands – that put experience literally at the centrepoint, with a higher density of products encircling each world.

Drummond says, “This truly experiential side of Hamleys World Moscow is created through different ‘Worlds of Play’, which take customers on a journey through nine worlds – in Motor City there is a Go Kart track; in Space children can test-drive the Millennium Falcon; in Magic Kingdom a huge castle in which kids can play and explore; and witches fly through Enchanted Forest on broomsticks, ducking between tree houses and scaling hidden pathways. This is a place for exploration and immersion, championed by a 13m tall LEGO rocket made with 1.9m bricks.”

Fitch drew inspiration from theme parks – particularly the perennial brand experience all-star Disneyland – in bringing toys to life. “Wherever you look, there’s not a shelf in sight with a dormant toy laying on it. It’s all about Iron Man alive and flying through the streets. We borrowed from theme parks. The navigation map looks a bit like a theme park map. There’s something around the experience – design for kids doesn’t have to be Scandinavian-type design,” says Regan. He points to supersensory experiences like the Rainforest Cafe that seem overwhelming to adults but are lands of immersive wonder for kids. That ethos was embraced in the development of the nine worlds in Hamleys. Immersion – for adults and kids alike – was at the forefront of experience design.

However, developing nine separate areas of play was the easy part, joining them together behind unifying design and experiential principles called for a refined organisational strategy. Fitch tried to avoid splitting toys and experiences up by gender. Age is the more relevant differentiator for young kids; the top floor is for babies and young kids while the bottom floor caters more to older children. Each world is linked by a yellow brick road and by toys that reach out toward their neighbours, joining different lands together.

Yet one of the major challenges was in breaking the mold of the standard warehouse store. Hamleys wanted to lead by experience, but it needed to get toy brands to understand its strategy. Brands had to understand why they were placed in a specific world or how they were allotted shelf space. “It was was a powerful concept at the start and we sold in the thought around collating brands by different experiential worlds. Once they understood that, they were happy to go ahead,” says Regan.

The store is designed to evolve. As brands’ popularity ebbs and flows, so too will the way the store is organised. The worlds will remain constant, but their amorphic brand zones don’t adhere to a square grid and are thus free to adapt to changing times. As Walt Disney once said, “Disneyland will never be completed. It will continue to grow as long as there is imagination left in the world.” That same imagination will drive the flexibility of the Hamleys experience.

For a global leader in toy sales, Hamleys has vast experience at developing a successful store. Yet, it also takes an interesting approach to localisation and to brand consistency – two concepts often at odds with each other. Though there are four other Hamleys locations in Russia, this flagship had a heritage all its own as it is set right in the heart of the Russian state.

“No toy should ever feel dead. It should be moving and alive thing. That’s what we’ve achieved here.”

Russian history and culture had to be acknowledged in Lubyanka Square. But, Fitch also had to ensure the brand icons and heritage shone through that local approach. The result is a leading example of how global brands can engage local audiences. “We were thinking, ‘Do we do the London brand in Moscow or do we want to be the London brand that’s tailored to Moscow so it has a sense of place?” says Regan. “It made a lot more sense to tailor it to Moscow and connect it to the people.” Fitch used imagery and visual techniques prevalent in the London flagship – like a frieze that runs around the store and London- based icons like the double-decker bus – but applied them to a Russian location. The bus, for one, was integrated into the space world where it was allowed to spurn its wheels and fly into space. The frieze used Moscow’s skyline, rather than the UK capital’s and Russian cosmonaut and hero Yuri Gagarin’s image is co-opted

to evoke a sense of Iron Man in space world. Russian fairytale character Baba Yaga finds a home in a life-size storybook house inside Hamleys. Finally, a giant Lego sculpture of Red Square completes the second-storey Lego world.

“This is officially the largest toy shop in Europe and we are honoured to have developed this exciting new experiential retail concept in such an iconic building and we have high hopes for this to become one of Moscow’s leading attractions,” Drummond says.

For Fitch and Hamleys, the new store is literally a dream come true – at least for the children who will be visiting it. By bringing fiction and fantasy to life through experience, Hamleys has paved a new – yellow brick – road forward in retail design strategy. Regan adds, “No toy should ever feel dead. It should be moving and alive thing. That’s what we’ve achieved here.” At Hamleys Lubyanka Square, its not just a figment of the imagination.